I went back to school last week. Granted, it was only for an hour and a half, but it was nonetheless quite the educational experience.

The occasion was Kristina Scott’s class on “Exploring Birmingham: Change and Power.” During what Birmingham-Southern College calls an “Exploration Term,” up to 16 students were encouraged to, per the catalog, “explore the social, political, economic and environmental forces that shape our city, and contemplate whether — and if so, how — Birmingham can fulfill its potential.”

That’s a tall order for a short term, but Kristina Scott might be uniquely suited to lead the safari. When she’s not educating the well-washed, Kristina is executive director of Alabama Possible, the current incarnation of The Alabama Poverty Project, founded in 1993 by historian Wayne Flynt, among others, to help ensure that the state’s haves would never disregard the have-nots. Educating the public is a big part of the effort to reduce poverty, and what better place to start than by educating the portion of the public that’s paying for the privilege?

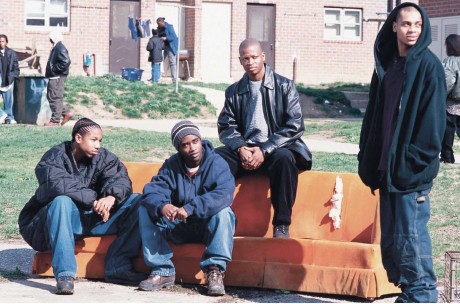

Already perhaps you feel your eyelids drooping at the prospect of examining Birmingham in this sort of detail, but Kristina had an eye-opening idea about approaching this curriculum. A fan of HBO’s legendary series The Wire, which was created by author and reporter David Simon to dramatize the plight of inner city America, she assigned the viewing of all 60 episodes to her class as a useful text for exploring Birmingham.

I always thought the stories of Omar and Stringer Bell provided object lessons. I just never thought they’d be taught in college.

There were five seasons of The Wire, and each dealt with a separate aspect of life in Baltimore; the drug trade, the docks, the city government, public education and print journalism. Is Birmingham like Baltimore? Well, Mayor Larry Langford failed to make us a seaport, but in every other respect, we match up. Baltimore’s a somewhat more expensive town to live in, according to a Bert Sperling survey, and although Forbes ranked us the 10th most dangerous city in America, Baltimore came in at number seven. With short fiscal resources and big problems to solve, the Magic City and Charm City face a lot of the same challenges.

For a discussion on media involvement in city life, Kristina invited me to join a panel that included the astonishingly energetic Rachel Estes, who works the community outreach beat for Canterbury United Methodist Church, and Steve Crocker, stalwart anchor of nightly newscasts on Fox 6.

The class had already engaged in many assorted field trips and walking tours, so this session around a table at Avondale UMC could have been either anticlimactic or blessed respite. There was no intellectual lassitude evident, though, and the class was ready to tackle city-sized issues, such as short-term thinking vs. long-term thinking, how to utilize limited resources and the tensions between idealism and realism.

There were a lot of high points in a brief 90 minutes. Rachel shared a story from her church family, about a kid facing the lure of easy money in East Lake drug traffic, which would have fit snugly in the narrative of The Wire. Steve reminded us that one of the takeaways from that series, as well as Breaking Bad, is that, in the process of making dreams come true, everybody gets compromised.

The students had good queries for the panel, thoughtful considerations of the many and complex aspects of urban life. One exchange in particular stuck with me:

Q: To revitalize the city of Birmingham, how can we find leaders with qualities we can trust, to know that they’re making the right decisions to help remake the city?

A: Be one. Why wait for anybody else?

Perhaps the best part of the session was afterwards, when the whole enterprise repaired to Bottletree for lunch. Being a working stiff, I had to beg off, but I wish I’d been in a position to give them some homework. A lingering question we didn’t get around to asking is just the sort of thing I think our future leaders should ponder, and it involves our present leaders.

What if it’s not possible to change things for the better?

When our systems of government became perilously corrupt around the turn of the 20th century, it took the combined efforts of social justice activists and political reformers to oust crooks from positions of power. History notes the successes at the top of the political food chain brought about by Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson and others so inclined, but the so-called Progressive movement started on the local level. Muckrakers helped expose corruption to the public, and change-minded citizens worked together to use the power of the ballot box to overturn the status quo.

A hundred years makes a difference. Though big money is still calling the shots these days, a weakened press and a cynical public can scarcely contend against it. For example, here in Birmingham, as in Baltimore or Biloxi or Bloomington, vote-influencing cash blows around the streets like pine straw each time an election comes up. You might hear scattered voices, but there is no assembly of the outraged calling for reform, and the rusting machinery of municipal government clatters on.

If people are so frustrated now by unresponsive government that they don’t want to participate in the process of changing it, democracy as we have known it is in jeopardy.

We’ve got World Games coming in six years, but what games will the city and county governments be playing with our money next week? How can our system be altered to help every neighborhood flourish, not just the ones that vote right? What can be done to make government responsive to ordinary citizens, not just the wealthy ones? These are the kinds of essay questions we all need to think about, not just the college kids.