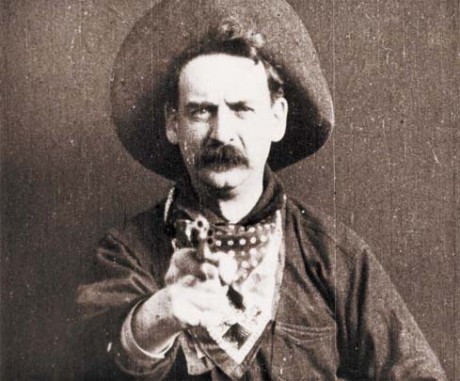

Attorney Will Meyers believes the U.S. should continue funding programs and other humanitarian efforts in Iraq that amount to more than just bricks and mortar, but “principles that will be sustainable in the long term.” Photo by Tom Gordon.

It might be hard to imagine that the legal system as we know it here, with courts, prosecutors, defense lawyers and clients and plaintiffs, applies anywhere today in war-ravaged Iraq.

From here, the country may seem like a toxic pharmacy with plenty of poisonous prescriptions. Hardly a day goes by when there’s not a news report of a bombing somewhere in Baghdad, killings of worshippers at a mosque, and attempts, sometimes successful, to kill or kidnap mayors, police chiefs, or other officials at the local or national level. And we have not even started talking about the ongoing depredations of the group known as the Islamic State, known as ISIS or ISIL, or the lethal legacies of the divisive, sectarian rule of the recent prime minister, Nuri Al-Maliki.

And this being the Middle East, aren’t a lot of people more loyal to the dictates of their tribal sheikh, their imam, or the tenets of their branch of Islam than what we like to call the rule of law?

Trying to establish an evenhanded system of justice which has support from all sectors of Iraq’s fractured society seems like the task that faced Sisyphus, the Greek mythological figure who was condemned to push a boulder up a hill again and again, only to see it tumble back to the bottom. But for most of the past 10 years, Birmingham attorney Wilson Myers has been involved in various aspects of just such an effort.

Myers is deputy chief of party with the Iraq Access to Justice program, a multimillion-dollar U.S.-funded effort that he says is designed to reinforce Iraqis’ belief in a formal system of justice, “to give them an outlet that does not result in violence.” A San Francisco-based management company, Tetra Tech DPK, is running the five-year program, slated to end in September. The $63 million program’s key components are legal clinics in which disadvantaged people can get assistance on legal matters.

“Only 12 percent of Iraq’s vulnerable people have access to the formal justice system,” the Access to Justice website states. “To bridge this gap, we support 28 grassroots legal clinics throughout the country to provide free legal services to those most in need. Together, these clinics have provided free legal services to nearly 14,000 vulnerable Iraqis.”

At present, however, the clinics are fewer while the numbers of justice-seekers have grown overwhelmingly, largely because of the Islamic State’s occupation of three northern Iraqi provinces and the country’s second largest city of Mosul last summer, and its efforts to wreak havoc in other parts of the oil-rich nation.

“Back before June 10, when ISIS invaded and took over Mosul … we were making great progress,” Myers said during an interview while on a late February visit home. “We had legal clinics in all 18 provinces of Iraq. The numbers were going up, people were feeling pretty good about themselves. We had some (legal) advocacy efforts and some awareness efforts that seemed to be taking hold, but then in June when ISIL invaded, it changed the dynamics of everything …”

The biggest change is hundreds of thousands of internal refugees who have flocked to Baghdad, Erbil, Karbala and other cities to get away from ISIS, and the various legal problems they bring with them are more than the justice system can handle.

“The system really was working better, but now, with the flood of internally displaced persons, the entire system is overloaded,” Myers said.

According to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, nearly 3.3 million Iraqis were internally displaced – forced to flee their homes while remaining in the country – as of Jan. 15. More than 2 million have been displaced just since December 2013.

Speaking of Mosul and its surrounding Nineveh Province, where U.S. regular Army and Alabama National Guard soldiers spent years working to improve security, repair infrastructure and other projects, Myers said, “It’s a tragedy. We’ve put a lot of money into courthouses, medical centers, schools. I mean, the U.S. government spent millions of dollars, if not billions of dollar in the Mosul and Nineveh area to build it up and … anything built by the U.S. has likely been destroyed. A number of very good people I knew have also been killed in Mosul – judges, government officials that I knew personally.”

Given these developments alone, what hope is there that the rule of law will take hold in Iraq?

“If a society does not have a faith and a belief in a justice system that works fairly – the rule of law, if you will – then society has some real challenges,” he said. “Even in our country, if you live in a neighborhood where there is no law, it is a horrible place to live. Is it easy? No, it’s not easy at all, of course. But is it worth it? I think so.”

And Myers takes heart when local officials with whom he has worked tell him about the good results Access to Justice is bringing to their communities. Sherzadazeez Sulaiman, dean of the law school at Salahaddin University in the Iraqi Kurdistan capital of Erbil, said in a Facebook message that the program helped the university set up its legal clinic “so they can receive a number of cases in a year to follow in the courts with the assistance of lawyers; it is a kind of legal aid that poor people are beneficiaries, and also students get practical experience from that, as well as some other related activities.

“I think that this program in this context is a very good job. Our students really benefited from this,” Sulaiman added. “We hope that we will be able to continue without their funds because the sustainability of this program depends on us. I really appreciate their efforts.”

Myers’ Iraq contract expires at the end of this month, and he’s set for another legal assignment, this time in Afghanistan. This assignment will mark the second time Myers has worked in Afghanistan, though the retired Army colonel and Cumberland School of Law grad has been in mostly in Iraq, off and on, since 2004.

Myers, who had a run as a Libertarian Party candidate for attorney general in 2002, was opposed to the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq in 2003, saying Iraq did not pose the threat to the U.S. that Taliban-ruled Afghanistan did. Then a friend he knew from the Army War College, “a significant player” in Iraq, contacted him.

“He said, ‘Why don’t you come over to Iraq for about six weeks and see for yourself?’” Myers said. “’We have some positions here that a lawyer can fill.’ Well, I was a blue collar criminal defense guy … at the time. Sounded pretty fun, it sounded exciting. So I said, ‘Sure, why not?’ So I went over for what I thought would be six (weeks) and now, 10 years later, I’m still doing it because … I just fell in love with the Iraqi people and I really believe that what we’re doing over there has value.”

For a few months in 2004, as part of the U.S.-established Coalition Provisional Authority, Myers was a legal adviser with the Iraqi Ministry of Justice and a senior legal consultant to the Iraqi Commissioner on Public Integrity, and helped train Iraqi criminal defense lawyers. Then he spent nearly nine months helping monitor and coordinate reconstruction in parts of Iraq for the U.S. State and Defense departments.

After some time back home with his family and his law practice – then in Bay Minette and Birmingham – Myers was back in July 2006, and stayed on and off for the next four years, working as a rule of law coordinator and senior provincial level rule of law adviser with U.S.-funded reconstruction teams in the Baghdad and Erbil areas.

In a letter he wrote to an imprisoned client before he began that assignment, Myers said he was closing his stateside law practice and expressed enthusiasm for what he was about to do in Iraq.

“As you know, I have spent 14 months there already,” Myers wrote. “The knowledge I gained then will hopefully help thousands of people realize the dream of a free, democratic society based on a recognized Rule of Law.”

After some time in Washington with the Justice Department, where his duties included working to establish more efficient and effective justice systems around the world, Myers spent more than a year in Afghanistan working primarily for two employers, the state Department and a California consulting firm named PAE Group, and coordinating with other organizations and groups on such rule of law-related projects as the training and mentoring of Afghan judges and lawyers.

As he prepares to depart from Baghdad, he harbors the hope that the Iraqi government will pick up the funding for the Access to Justice clinic program when its U.S. funds run out. In his view, the U.S. should continue some funding for the program and other humanitarian efforts in Iraq that amount to more than just bricks and mortar, but “principles that will be sustainable in the long term.”

“Those principles are international rule of law principles, you know.”