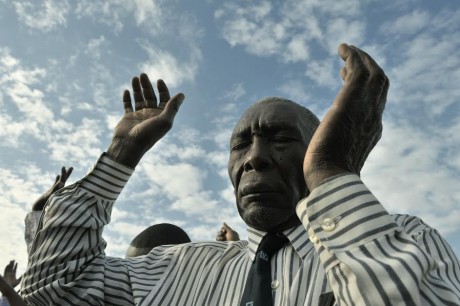

Whereas Millennials have shied away from religious institutions, research indicates they remain relatively traditional in other religious categories, with 75 percent of Millennials believing in life after death. Photo courtesy of triconphotos/Flickr Commons.

“It’s a wild world that we find ourselves in,” Joe McKeever said as he rolled the question of salvation around in his head for a moment.

Everything seems to be moving at a frantic pace and everyone wants different things from religion and church, McKeever said. “Who is right and who is wrong is hard to say.”

Should one be Catholic? Or should one be Buddhist? Who is right and who is wrong?

McKeever will tell you, spirituality, religion and being a good person isn’t a single right or wrong question. It’s a long-form essay. The most important thing is just to practice what you preach, he said.

McKeever’s been a Baptist preacher since 1962. He got his start as a pastor at West End Baptist Church in Birmingham. Since then he has traveled all over the South spreading the gospel to various congregations in Alabama, Louisiana and Mississippi. But today something is on his mind that he can’t seem to shake. The idea of church seems to be changing, he said.

He was talking about the influence of the megachurch.

“I recently went with my son to a church in North Carolina that probably has about 10,000 people attend every week,” McKeever said. “Frankly, I was horrified. There was nothing about that experience that I liked. They had earplugs when you walked in, and, boy, did I need them. I felt like I was being assaulted by the band.”

McKeever went on to explain that the preacher told stories about himself and lauded his own accomplishments. At one point he even joked about how much he was talking about himself.

“I don’t remember him mentioning Jesus one time,” McKeever recalled.

The main issue McKeever takes with the megachurch movement is that he believes the productions they put on can spoil people, especially young people, to the point where the traditional concept of church seems drab and outdated. Smaller, community churches often have to compete to retain young membership against such massive, contemporary congregations.

Perhaps McKeever embodies the generational gap that exists between the old guard and the new. Megachurches aren’t for everyone, he said, himself included.

On the other hand, those who attend megachurches say they offer a breath of fresh air and show the way churches should be operating in the modern world. They continue to draw the attendance of younger people, while traditional churches seem to cater to an older generation, like McKeever.

A recent study conducted by Pew Research indicates that Millennials, that is, people born from 1981 onward, are the least religious generation by a substantial margin. However, while Millennials appear to be unmoored to religious institutions, they also remain fairly traditional in other ways and seem to be flocking to the contemporary offerings of the megachurch movement.

So what does this exodus from traditional religious institutions mean for the future of church?

The Fourth Ave. South Baptist Church, which sits atop a crest overlooking downtown Birmingham, is an example of a traditional church that has remained unchanged for decades. Photo by Cody Owens.

Faith in numbers

The Pew Research study, “Religion Among the Millennials,” concluded that 26 percent of Millennials have shied away from religious affiliation, a far cry from their Baby Boomer elders.

According to the study, “Millennials are significantly more unaffiliated than members of Generation X were at a comparable point in their life cycle (20 percent in the late 1990s) and twice as unaffiliated as Baby Boomers were as young adults (13 percent in the late 1970s). Young adults also attend religious services less often than older Americans today. And compared with their elders today, fewer young people say that religion is very important in their lives.”

One-in-four adults, 25 percent, under the age of 30 identified themselves as “atheist” or “agnostic” or “nothing in particular.” As for people over 40, 15 percent placed themselves in this category. And for people 60 and over, less than 10 percent responded this way.

The data indicates this is not based on age difference alone. It’s not just that when people age they tend to become more religious. Rather, the study says, “Data from the General Social Survey, which have been conducted regularly since 1972, confirm that young adults are not just more unaffiliated than their elders today but are also more unaffiliated than young people have been in recent decades.

De’Andre Salter, senior pastor of the New Jersey-based Tabernacle Church offered his opinion on why more young people aren’t going to church.

“I think the church is failing to address the issues that are important to Millennials,” Salter said. “Millennials tend to be cause-focused versus community-focused. Baby Boomers were about all about doing things in community and in their secluded neighborhoods while Millennials are more focused on a multitude of causes that effect a wider range of people.”

One of the key differences that Salter pointed out between Millennials and the Baby Boomer generation is that they care strongly about different issues. It’s not surprising, given the recent upheaval of laws that previously restricted gay marriage, that Millennials are much more accepting of homosexuality than previous generations, as indicated in the study.

Beyond that, Salter continued, the traditional church has failed to engage younger people about the issues that concern them — one of the biggest issues being economic inequality.

“They are one of the smartest generations ever, but they are displaced from the workplace by and large, and, therefore, they have a greater economic frustration than the Baby Boomers did when they were their age,” Salter explained. “And that’s just one of the issues that the church is missing a large opportunity on addressing with Millennials.”

McKeever told a story about preaching one Sunday at a small church in the suburbs of New Orleans.

“The pastor there told me he was worried about not being able to get younger people to come to church,” Mckeever said. “I told him, what his church has to offer is some of the loveliest people I’ve ever met. I said just be that. Be yourself and be genuine and young people will come.”

The study does after all indicate that while Millennials have shied away from church, they remain relatively conservative in other aspects. Because of this, McKeever believes the young people will eventually turn towards smaller churches once the megachurch movement reaches “critical mass.”

The big question of life after death is one example of traditional beliefs being shared between generations.

“Adults under 30, for instance, are just as likely as older adults to believe in life after death (75 percent vs. 74 percent),” according to the study.

However, people in both age groups are less likely to believe there is a hell as opposed to heaven.

The study also indicates that all age groups agree in absolute standards of right and wrong.

“For instance, more than three-quarters of young adults (76 percent) agree that there are absolute standards of right and wrong, a level nearly identical to that among older age groups (77 percent),” the study reads.

In spite of some of the traditional beliefs that have crossed generations, young people are flocking in droves to large, non-denominational churches and leaving behind the ways of the traditional church.

Why we left

During the last installment of the “Evolution of Church” the Church of the Highlands served as an example of how megachurches are operating in the modern age. With 14 locations that have been developed in just 15 years, COTH has seen unparalleled growth and prosperity in a relatively short amount of time.

After the story was published, a multitude of responses came pouring in from COTH members wanting to explain why they left their smaller churches and the life changing experiences they have encountered since upsizing.

William Sledge, a 29-year-old father of two, said that he grew up in Greensboro, Alabama and attended a small church for most of his adolescence. It was a typical small town church that peaked in attendance well before he was born, according to Sledge.

“There are benefits of being involved in a small town church,” Sledge explained. Everybody knows you, who you are, who your family is and who your grandparents are and so on… There is a lot of what I would call ‘family loyalty’ when it comes to choosing a church in a small town. You pretty much go where your grandparents went.”

This can lead to a burdensome feeling and an unnecessary sense of obligation, Sledge continued.

“I didn’t go to church much throughout high school and my youth,” he said. “After my wife and I got married we lived in the Tuscaloosa area, and we began to look to for a church that made us feel at home. We also wanted to be involved in a congregation that we felt were making a difference in the world.”

Sledge also mentioned the fact that today’s young people seem to have a sensational drive to want to make an impact on the world. Often, he said, this drive can be stifled in a small congregation.

“It is hard for a small church of less than 100 members to appear to change the world when they can barely afford gas for the church bus,” Sledge said. “When you are involved in a very influential church you feel that your volunteering and money goes to really bringing people to Christ and changing the world. I know our church really shows the congregation where their money is going and how it is making an impact on people’s lives.”

Like many, Sledge was taken aback by the carpet of devastation that was laid down across Alabama in the wake of the April 27, 2011 tornado outbreak. He was living in Tuscaloosa at the time.

“I felt that my community needed my help so I went to the devastated area and volunteered to help,” Sledge recalled. “When I got down there I was blown away by the devastation. I saw an army of people wearing these red shirts that said ‘SERVE’ on them. I was curious as to where they came from. I assumed it was a division of Red Cross or something. Come to find out, they were all members of Church of the Highlands. That day I knew I wanted to be involved in a church that could get people mobilized and motivated to take to the streets in the name of Christ.”

Trisha Tomlin has a similar story of her departure from a small community church that she said did not allow her to grow spiritually. Like Sledge, Tomlin now attends the COTH.

“For me,” Tomlin said, “I know the pastor, Chris Hodges, hears from God [and] believes in all the gifts and in spiritual warfare and desires that all believers grow and serve in their gifting. God told me this is where he wants our family right now and we are being obedient… The traditional church I went to seems to have been heavy in law and absent with the spirit.”

However, Tomlin does not write off the merit of smaller congregations completely. For her it’s less about the size and more about the flavor.

“It has to do with content, style and flavor,” Tomlin explained. “For example, I know of another smaller church in Birmingham that allows more open demonstration of the things of the spirit. While they are no where near the size of Highlands, their worship style and the freedom they give the spirit to move during service cannot be done at Highlands due to Highland’s Sunday service model of it being outreach-based. I think that if I lived in Birmingham I would probably be more drawn to that smaller church where the spirit was allowed to move more freely. But I live in Montgomery and God told me that he wants me here at Highland.”

About 15 years ago, Rev. Angie Wright decided Avondale would be the perfect place for her community church, located at the crossroads between one of the countries most affluent zip codes and one of the poorest. Photo by Cody Owens.

Once a beloved, always a beloved

Nestled next to the Avondale Brewery sits the Beloved Community Church, an unassuming two-story building with a brick façade.

One Sunday night, before the service began, music from a concert at the brewery crept uninvited into the worship hall. The band next door was playing a cover of Led Zeppelin’s “Over the Hills and Far Away” as parishioners started to file in for the Sunday evening service.

Not long afterward, all unwanted noise was drowned out as the worship band started up and the 30 or so parishioners joined in on some old-fashioned hymns. Everyone sang along, even the children. It seems like a world away from the worship service McKeever described needing earplugs to make it through.

The Rev. Angie Wright founded the Beloved Community Church 15 years ago. When it began Avondale was not the trendy little nook it is today.

“You go a half mile in that direction,” Wright said, pointing over Red Mountain, “And you got one of the most affluent zip codes in the country. You go a half mile in the other direction and you have one of the poorest. We just thought this was a great crossroads for a place to create a diverse church.”

Wright wants her church to be a place where humanity can be affirmed. She openly welcomes people as they are and has become a strong advocate for social issues she believes are keeping the state stuck in the past, like civil liberties, LGBT rights and Medicaid for the poor.

“We believe in helping people where they are, but we also want to challenge things in society that take away people’s humanity,” Wright said.

During the Sunday’s sermon, Wright urged the congregation to call their state representative and tell them to vote against Senate Joint Resolution 34 that would prohibit the expansion of Medicaid in Alabama.

The congregation at Beloved seems to be much more representative of its community than, perhaps, a larger congregation that lacks the same racially diverse patronage. Because of this, Wright said, there is a big focus on the troubles of racial inequality and what the church can do to help.

Despite what Sledge said about the inability small churches have to “affect the world,” Beloved tries to do its part for the neighborhood. Grocery bags filled with food line the perimeter of the downstairs space.

“We’re doing a food drive for the children who are out of school for the summer,” Wright said. “Because they aren’t getting school breakfast and lunch, summer is a time when hunger hits the hardest.”

Leah Clements has been going to Beloved Community Church for over a year. Clements also falls under the umbrella of the Millennial generation. She said she started attending the church because of the racial diversity and the honesty behind each message.

“I was drawn to a multiracial church and the incredible R&B soul music, which draws in people across race and class, something that is really hard for churches to overcome for some paradoxical reasons,” Clements said. “I was delighted to hear a woman preaching and befriending such an eclectic mix of people. And I knew that my strange soul would mix right in. Also, there was an open conversation about mental health, and I appreciated the raw honesty.”

Clements highlighted a point that McKeever also made about megachurches when talking about her aversion to massive congregations.

“Small community churches dismantle the pastor-as-savior complex which many megachurches generate,” Clements explained. “In other words, the relationships developed with leaders and ‘lay people’ alike are closer and messier, enabling vulnerability and accountability on all levels. Beloved in particular, by proclaiming everyone to be beloved the moment you walk in the door, generates a collective sense of participation and belonging. This piece is vital for any community church to thrive — to build up the regulars while embracing the newcomers.”

Does Clements foresee her peers as becoming a godless generation who completely shun the church? Not at all. Rather, she thinks her own experiences reflect the nature of today’s younger generation and why they have become untethered to religious institutions.

“As someone leaving Birmingham soon, and having spent time at Beloved and a six-month stretch not at Beloved, I think my experience sheds some light,” Clements said. “Millennials are transient, usually shifting between jobs and cities, moving around their loyalties and commitments. I’m not sure this needs to change. Perhaps it’s more important for church leaders to engage this transient generation where they are.”

“We are also not entirely convinced that emotionally held belief systems we grew up with hold up beneath our newfound 20-something scrutiny,” Clements continued. “Beloved, with its political activism and varied demographic is not perfect, but I find that people respond to my curious scrutiny with thoughtful care, which is refreshing in the war-zone that is Southern religion.”

And in that war-zone, Clements said, megachurches may serve as the generals, but the small community churches, the ones with the boots on the ground in the middle of the fray, are the medics tending the wounded and weary.

So what does the future of church look like? Will more people join megachurches, eventually leading to the extinction of small community churches that struggle to retain young members? Wright doesn’t think so.

“I think there is always going to be a spectrum,” Wright said. “I hear people say if a church isn’t growing, it’s dying. And I just wholeheartedly disagree with that. It’s all about the work you’re called to do. You’re not going to find any megachurches in the inner-city. That’s where the need is and that’s where we are.”