The past couple of months have seen the release of three books by authors with Birmingham connections. Writers T.K. Thorne, Joe Samuel Starnes and Doug Wedge have drawn generally favorable reception for their respective new works.

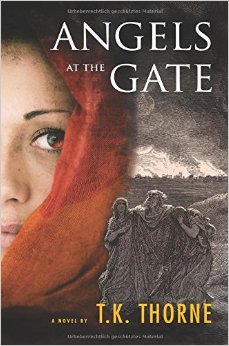

Thorne’s Angels at the Gate is her second novel. The first, Noah’s Wife, earned national attention for its compelling narrative and blending of historical facts and locales with spiritual themes and contemporary issues. Foreword Reviews, which focuses on works from independent publishers, named it “Book of the Year for Historical Fiction” in 2009.

Thorne’s Angels at the Gate is her second novel. The first, Noah’s Wife, earned national attention for its compelling narrative and blending of historical facts and locales with spiritual themes and contemporary issues. Foreword Reviews, which focuses on works from independent publishers, named it “Book of the Year for Historical Fiction” in 2009.

Thorne — a retired captain of the Birmingham Police Department and currently director of the City Action Partnership, which provides public safety services in downtown Birmingham — also is the author of the nonfiction book Last Chance for Justice, an account of how the uncovering of new evidence led to the convictions, nearly 40 years after the fact, of the two surviving perpetrators of the 1963 bombing of Birmingham’s Sixteenth Street Baptist Church. Among other recognition, that book made The New York Post’s list of “Books You Should Be Reading.”

Like Thorne’s previous novel, Angels at the Gate defies easy categorization. Yes, it’s “historical fiction,” set as it is in ancient Biblical times, around the story of the destruction of the wicked cities of Sodom and Gomorrah. But in spinning a “backstory” for the well-known tale of the wife of Lot, whom the Bible tells us was turned to salt for defying God’s command not to look back at the devastation as she fled with her husband and family, Thorne combines exhaustive research of the people, places, religious beliefs and customs of the times — the 18th century BCE — with her considerable abilities as a storyteller, a raft of fully realized characters, and a strong feminist subtext to create a book that transcends the confines of the genre.

Unnamed in the Bible, Lot’s putative wife here is Adira, whom we meet as a girl on the cusp of womanhood, and who has carried a lifelong secret. That secret is revealed to the reader in the book’s opening paragraph, which Thorne uses to set the tone and draw the reader into the story that follows:

If the path of obedience is the path of wisdom, it is one not well worn by my feet. I am Adira, daughter of the caravan, daughter of the wind, and daughter of the famed merchant, Zakiti. That I am his daughter, not his son, is a secret between my father and myself. This is a fine arrangement, as I prefer the freedoms of being a boy.

Starnes, the author of Red Dirt — subtitled A Tennis Novel — was born in Anniston, but moved with his parents to Georgia, the book’s primary setting, when he was a year old. Originally a journalist by education and trade, he has taught writing at several colleges, and now works in the administration of Widener University in Delaware. His Birmingham connection is through his brother, Dan, who is the publisher of the local community newspapers The Hoover Sun, The Homewood Star, The Vestavia Voice, Village Living and 280 Living.

Starnes, the author of Red Dirt — subtitled A Tennis Novel — was born in Anniston, but moved with his parents to Georgia, the book’s primary setting, when he was a year old. Originally a journalist by education and trade, he has taught writing at several colleges, and now works in the administration of Widener University in Delaware. His Birmingham connection is through his brother, Dan, who is the publisher of the local community newspapers The Hoover Sun, The Homewood Star, The Vestavia Voice, Village Living and 280 Living.

Red Dirt is Starnes’s third novel. His previous work, Fall Line, published in 2011 by Montgomery-based New South Books, was included The Atlanta Journal-Constitution’s “Best of the South” selections for that year.

The title of Starnes’s new book refers to both the red clay topsoil of his native Georgia, and to the clay tennis courts where much of the novel’s action takes place. It’s the story of Jaxie Skinner, who rises from a blue-collar background to become a world-class tennis player. Skinner briefly achieves global fame at the age of 18, after a remarkable run at the French Open, one of the four major tournaments in professional tennis. He then experiences a series of setbacks that cause him first to quit the game for a decade, and then spend another 10 years scuffling anonymously in its lower echelons, seeking some kind of personal and professional redemption for the career he squandered.

Red Dirt is both an absorbing character study and a fascinating glimpse into the world of pro tennis. Starnes, himself, was a fine junior tennis player, and he uses his knowledge and continuing love of the game to fine effect throughout. The pre-match musings of the older, wiser Jaxie, fighting his way back to prominence, demonstrates Starnes’s mastery of his subject, as well as the understated style he brings to telling this particular story:

But I could afford no respect for his game when we were on the court. I had played enough matches in my life by then to pick out what would beat him. I was playing a very cerebral game, thinking about how to break the players down, just as willing to take an error from my opponent as I was to hit a winner.

The nonfiction entry in this trio of Birmingham-connected books is The Cy Young Catcher. It’s a collaboration between Birmingham attorney Doug Wedge and former major league catcher Charlie O’Brien, who happens to be Wedge’s brother-in-law. Dedicated baseball fans — including this one — might recall O’Brien as a journeyman catcher who spent 15 years in the bigs, playing for eight different teams between 1985 and 2000. Others may know him as the “inventor” of the hockey-style mask that most catchers wear today.

The nonfiction entry in this trio of Birmingham-connected books is The Cy Young Catcher. It’s a collaboration between Birmingham attorney Doug Wedge and former major league catcher Charlie O’Brien, who happens to be Wedge’s brother-in-law. Dedicated baseball fans — including this one — might recall O’Brien as a journeyman catcher who spent 15 years in the bigs, playing for eight different teams between 1985 and 2000. Others may know him as the “inventor” of the hockey-style mask that most catchers wear today.

Neither of these things is the real impetus for the new book, though Wedge says he was compelled in part by telling the story of an everyday player who was not a star (O’Brien’s career batting average was a less-than-eye-popping .221), and yet enjoyed a long career due to his ability to work with pitchers. That ability is underscored by the rather remarkable fact that gives the book its title: During his career, O’Brien was the battery mate for 13 pitchers who won the Cy Young Award, which is given annually to the top pitcher in each league.

Accordingly, The Cy Young Catcher is presented in 13 chapters, one for each pitcher. Each opens with comments about O’Brien from that pitcher — Greg Maddux says O’Brien “knew the hitters as well as any catcher I’ve ever thrown to,” while Roger Clemens relates that, “My son is a catcher, and I tell him to watch tapes of Charlie…to study how the position should be played.” — followed by O’Brien’s reminiscences of working with that pitcher and his straightforward, frequently profane, and very often amusing insights into pitchers, catchers, and the game in general.

There’s a lot of “inside baseball” stuff that true fans will love. In the Maddux chapter, the book tells of once when O’Brien had moved on from being Maddux’s teammate in Atlanta and was playing for the Toronto Blue Jays, and how, in a game against the Braves, he used his knowledge of Maddux’s tendencies to help a new teammate heading up to face the Atlanta ace:

I told Shawn Green, a left-handed hitter, that if he was hitting against Greg with no base runners on board, he should look for a pitch sequence of a fastball away, a cutter inside, a fastball that runs back inside, and a changeup. If there were base runners, Greg might throw a cutter inside, then two changeups.

Sure enough, Shawn spotted the pitches. Hit a home run. Shawn thanked me for it. I felt kind of bad about that, but at the same time, I’m competitive. I wanted my team to win. I’d help however I could.

A previous version of this story stated that Samuel Starnes works at St. Joseph’s University. He actually works at Widener University.