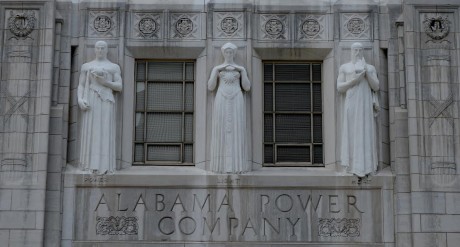

Built in 1925, the Art Deco-style building that serves as Alabama Power’s headquarters is one of the more iconic architectural structures in downtown Birmingham. The carvings above the entrance represent power, light and heat. Photo by Cody Owens.

Do Alabamians living below the poverty line pay too much for electricity?

That depends on whether you ask Alabama Power or one of the agencies in Birmingham trying to aid underprivileged individuals and families.

The question was raised in a study published by the Greater-Birmingham Ministries, which indicated in 2013 Alabamians spent 4 percent of their median income on electricity rates — the highest percentage of any state.

Alabama Power, however, contends that their rates are 12 percent below the national retail average. In response to the GBM study, Alabama Power released a statement contending that the “figures and citations in their document are flatly wrong; others are used in misleading ways.”

The conflict draws a sharp line between the electric utility and a nonprofit that Alabama Power has supported in the past with financial contributions. The current state of the relationship between GBM and Alabama Power is mentioned in a rebuttal from the utility.

“We must note a history of financial contributions to GBM,” said a statement by Michael Sznajderman, a spokesperson with Alabama Power. “However, their two most recent requests were rejected as they directly duplicated services we were already supporting through established agencies.”

The majority of the statement, however, seeks to refute the claims GBM makes that Alabama Power charges too much and the Public Service Commission (PSC) turns a blind eye to it.

“Now, more than ever, the [Public Service Commission] institutes policies that are in no way equitable or economic for customers…and in doing so harm Alabama families, especially in low-income communities where inability to pay utility bills can lead to eviction and homelessness,” said the GBM study. In December 2014, the study notes, the PSC approved a 5 percent increase in the electricity rates for Alabama Power customers.

“This decision was business as usual; the decision was made swiftly, with next to zero discussion of whether the expenditures the utility said it needed were prudent or even necessary,” the study reads.

Scott Douglas, executive director of GBM, said that the decision to conduct the study came about as a way to open a dialogue and stimulate the conversation for a comprehensive Public Service Commission reform.

“This study isn’t about the most recent increases in the utility rates,” Douglas said. “It’s about the incompetence and inability exhibited by the Public Service Commission to do the job they were elected to do, and that is regulate these things.”

Alabama Power responded by defending its own corporate actions. “The costs associated with making and safely distributing electricity have increased for all utilities over the past few years,” said Sznajderman’s statement. “With the encouragement of the Alabama Public Service Commission, Alabama Power consciously delayed rate adjustments for three years, specifically because of the impact on customers in a down economy. Despite GBM’s claims, Alabama Power’s adjustments were in direct response to cost pressures felt throughout the entire industry.”

The GBM study also makes note of the economic downturn that began in 2008. At the beginning of 2007, the study reads, unemployment in Alabama was 3.9 percent, but it peaked in 2009 at 11.9 percent. As of December 2014, however, the number was back down to 6.1 percent, although the impact of the economic recession can still be felt in Alabama, according to the study.

“Overall poverty in Alabama jumped significantly from 2007 to 2013, increasing the number of Alabamians living below the poverty line by 139,000 people and boosting the overall poverty rate from 16.6 percent to 18.9 percent of the population,” according to the GBM study. “At the end of 2013, more than one out of every four children under 18 in Alabama lived in poverty.”

Sznajderman said there are several factors contributing to Alabamians’ high usage of electricity.

“The fact that customers tend to have higher electricity bills in Alabama is a function of the amount of electricity they use. Electricity usage is higher in Alabama, for three reasons,” Sznajderman explained. “One, we have very long, hot, muggy summers in Alabama, with people using a lot of air conditioning over many months. We have extraordinary penetration of electric heat pump usage in our state, meaning many people are using electricity for both summer cooling and winter heating. Finally, people are choosing to use electricity because it is a good value compared to other options for heating and cooling,” Sznajderman said.

Sznajderman also said that according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration data, while household consumption of electricity is high in Alabama, the state’s residential consumers use less total energy in their homes on average than most residential consumers in other states.

“In other words, when it comes to total energy usage, Alabamians are actually pretty energy efficient,” Sznajderman said.

Perhaps the main point of contention that Alabama Power has with the study, Sznajderman said, is GBM’s allegation that Alabama Power does not have enough invested in energy efficiency programs to help low-income users.

“We offer more than 20 different energy-efficiency and demand-management programs for residential, commercial and industrial customers,” Sznajderman said. “Those programs have resulted in over 1,800 megawatts of demand reduction. That is the equivalent to the electrical demand of over 500,000 average residential homes in our service territory.”

The GBM study does not blame the increased rates entirely on an effort to maximize profit by Alabama Power. “Instead the true blame for the inequities in the current system rests squarely on the shoulders of the Alabama Public Service Commission,” the study reads.

Representatives for the Alabama PSC declined to comment.

From 2007 to 2014 the PSC approved plans that saw Alabama Power’s retail revenues increase across all classes of customers — residential, commercial and industrial — by 18.6 percent. This means that for every kilowatt-hour sold, customers paid an average of 1.45 cents more, according to the study.

“In addition to covering the cost of compliance with pollution-control laws, raising rates is also a surefire way to boost profits,” according to the GBM study. “Alabama Power’s net income after taxes and dividends rose steadily from 2007 to 2014, increasing every year but one, from $580 million to $761 million, a generous increase of 31 percent. Much of that profit is attributable — in the company’s own words — to higher retail revenue coming from rate increases.”

Alabama Power contends, however, that the increased rates are attributed to the cost of keeping in line with pollution control regulations.

Despite the claims made by the GBM study, not all organizations that work with the poor see Alabama Power as a negative influence. Marquita Davis, executive director of the Jefferson County Committee for Economic Opportunity (JCCEO), described Alabama Power as a valued partner in the fight to alleviate the pressure of utility bills for low-income families.

“The idea is more focused on moving people towards self-sufficiency, but that looks different than just continually helping people,” Davis said. “With our energy efficiency programs, we’ll help get people’s bills paid but also provide financial literacy counseling.”

Along with financial counseling, JCCEO also helps with funding for Low Income Heating and Energy Assistance (LIHEAP), which, as a result of the economic recession, saw massive increases in funding from 2007 to 2010.

According to the GBM study, federal assistance to help people pay for electricity and heating more than tripled during this time period, from $22.2 million to $69 million in Alabama. In 2014, funding for LIHEAP in Alabama was cut back to $48.9 million.

Davis said that the JCCEO, with funding through Alabama Power, is focused on helping families who don’t necessarily qualify for LIHEAP.

“Alabama Power has been a great partner with our community action programs,” Davis said. “ABC Trust, set up by Alabama Power, provides financial support to our agency for individuals who may not meet all of the requirements for LIHEAP. You may have individuals who may not meet all of those requirements but they are still in need of energy assistance. They may have several children or what have you.”

“We are provided money every year through that fund for people who don’t qualify for LIHEAP. If we didn’t have that help there would be craziness in the streets because these are desperate times for us and the people we serve. So I would say their partnership is a godsend,” Davis continued.

The GBM study concludes by asking Alabamians to question their elected officials and pay attention to what they called the “rubber-stamping” oversight of the PSC.

“No one is questioning the safety, adequacy or reliability of electricity in Alabama,” the study reads. “It’s patently clear, though, the [PSC] has instituted policies that are in no way equitable and economical for customers. The PSC’s decisions harm Alabama families, especially those of low income, at the same time they boost the bottom line of a monopoly utility that the commissioners are supposed to hold in check for the people of Alabama.”

Read Alabama Power’s full rebuttal here.