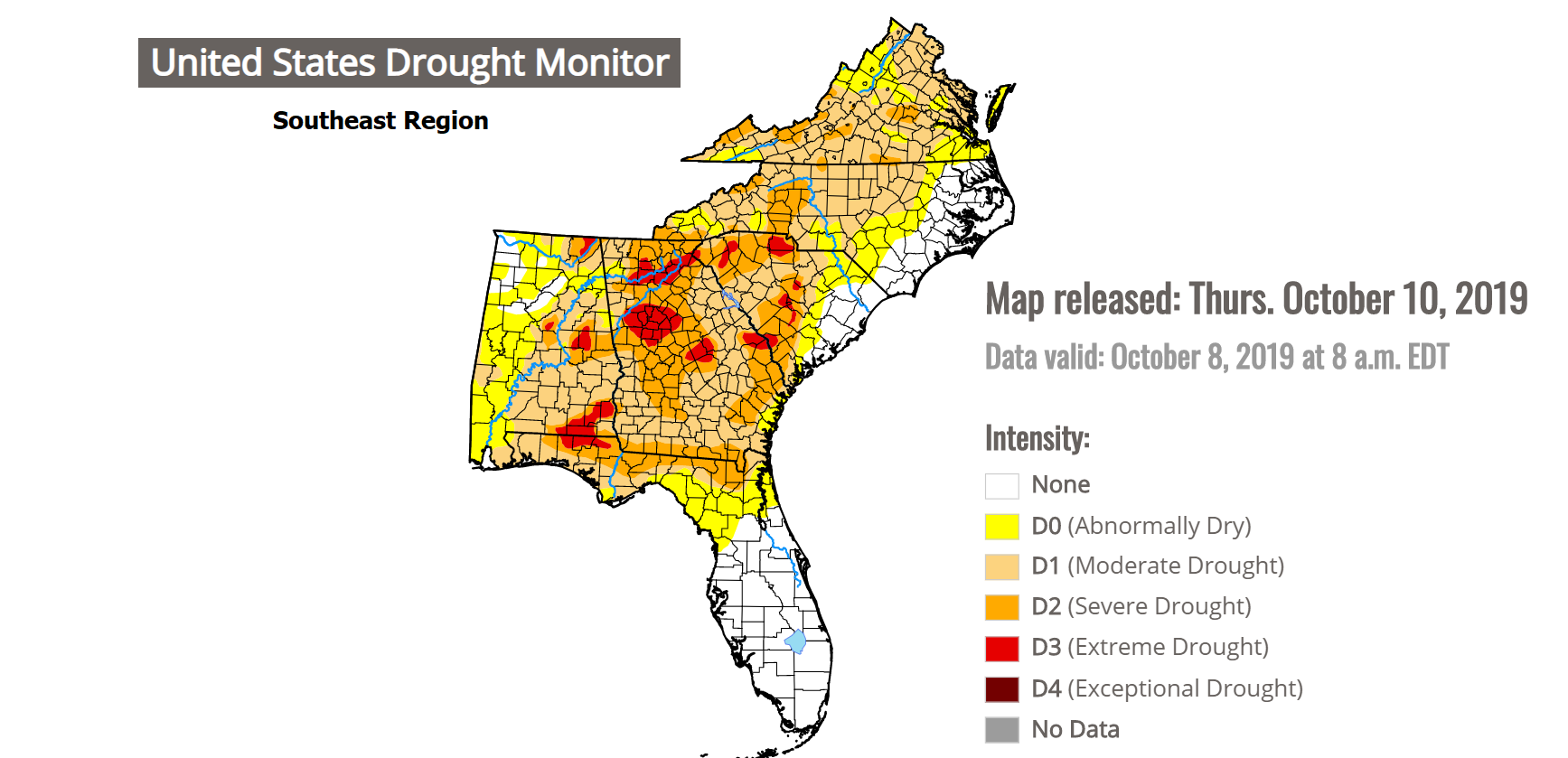

CARTERSVILLE, Ga. (AP) — Across a vast expanse of the South stretching from Texas to Maryland, there are growing concerns for the cattle, cotton and corn amid a worsening drought fueled by this summer’s record high temperatures.

One of the bullseyes marking the nation’s driest areas is Bartow County, Georgia, where extreme drought has kicked up buckets of dust and left cattle pastures bare. The farm country northwest of Atlanta is among the hardest hit spots in a dozen Southern states where more than 45 million residents are now living in some type of drought conditions, the most recent U.S. Drought Monitor report shows.

“Looking ahead if we don’t get enough rain and the pastures don’t recover, we’ll be dipping into winter feeding hay before time, or have to liquidate some cattle,” said Dean Bagwell, a cattle farmer in Bartow County.

“It is frustrating with the weather, complicated by cattle prices not as high as we’d like to see them,” he said. “So if you are forced to sell, then you’re going to have less income. It just all plays into the frustration of trying to make a living farming.”

At a farm where people come to see the kangaroos, camels and other wildlife in Cartersville, Georgia, owner Scott Allen points out the “baked mud” and cracked earth in the bed of a small stream near his zebras. The natural spring water is nearly dried up, so he’s using municipal water.

“It’s been probably better than 60 days since we had any precipitation that amounted to anything,” Allen said. “The dust is just relentless.”

The USDA crop report shows nearly a quarter of the cotton crop is in poor or very poor condition in Texas, where more than 13 million people — more than half the state’s population — are experiencing drought conditions, the center reported. Extreme drought spread into several new areas of central and eastern Texas in recent weeks.

The situation is also dire in North Carolina, where 40% of the cotton and 30% of the corn is in poor or very poor shape. In Georgia, nearly 20% of the peanut crop is in poor or very poor condition, the report shows.

The heat has played a large factor, forecasters say. In August, high temperatures and humidity sent the heat index soaring across the South. The heat index — what it actually feels like — rose to 121 degrees (49.4 Celsius) in Clarksdale, Mississippi, on Aug. 12. And that heat stuck around, carrying record high temperatures into October. Several Alabama cities this year have seen their hottest October temperature ever recorded.

The combination of dry weather and intense heat can create drought conditions relatively quickly, resulting in a “flash drought.”

The term came about during a 2001 drought in the Great Plains. Mark Svoboda, director of the National Drought Mitigation Center, was looking for a way to describe the rapid onset of that drought and came up with “flash drought,” he recalls. The phrase resonated with people and made headlines in The Omaha World-Herald’s coverage of that drought. Back then, Svoboda and other scientists had few tools to track flash droughts. Within the past decade, however, satellite imagery has given forecasters much better data to monitor a rapidly-spreading drought, Svoboda said.

In coming years, climate change is expected to intensify droughts and increase their frequency, scientists warned in the National Climate Assessment released by the White House last year. And heat waves are expected to hit the South harder than other regions.

Cities with a particularly high risk of future heat waves include Memphis, Tennessee; and Raleigh, North Carolina. New Orleans and Birmingham, Alabama, are also cited in the report as having trends toward more intense and frequent heat waves.

A new report on the drought is expected later Thursday showing the damage already done, but now Bagwell and other farmers are concerned about the long-term outlook. Octobers are usually among the driest months in the South. There is one hope for farmers: Long-range forecasts point toward above-normal precipitation in the Southeast later this month, according to the Climate Prediction Center.

At the Tri-County Gin in Cartersville, one of the last remaining cotton gins in north Georgia, dust from the Georgia red clay coats the pickup truck where owner David Smith peers over the steering wheel and ponders the dry conditions.

“It’s not a complete, overall disaster, but there are places that are hurting bad,” he said.